SUPERHERO SUITS, the science behind the world's most aerodynamic suits

Deanna Panting is the founder and CEO of Qwixskinz, a Canadian company highly specialized in high performance race suits for all kinds of sports. With a not-so-negligible athletic background- eight years of World Cup Skeleton racing on the Canadian National team, winning World Cup medals in all colors- she brings her knowledge into the race suit research and production, having now more than 20+ years of experience in the race suit industry, providing the fastest suits to many athletes, Olympics to provincial level, with an impressive team of aerodynamic and scientific experts, state of the art fabric developers and world leading designers.

INTRODUCTION

Livia: Tell me a bit about your athlete background and career path that led to becoming one of the leading race suits designers today.

Deanna Panting: It is quite a strange kind of path. Basically, I grew up in an athletic family, and I was always in sports: I was brought up as a speed skater, and then I moved to track and field and strength sports. Until I ran into a friend of mine after the Albertville Olympics in 1992, who told me "Go to Calgary, they are starting to do women's bobsleigh. You are fast. You are strong. You'd be good at it." A month later, with my cat and my bicycle in the car, I drove from Winnipeg to Calgary, phoned one of the 2 phone numbers I was given and started racing bobsleigh. While I was doing that, someone else told me I should try skeleton. In bobsleigh, I was a brakeman and I sat in the back, doing nothing but pushing and putting my head between my knees. It probably didn't help that I was pregnant with my son at the time I was racing, so I was not feeling great. After I had my son, I started racing skeleton. During that time there was a small race suit company in Calgary that I began working with while still an athlete. That was soon sold, so I started my own company with the head pattern maker and the head sewer from that original company. The first Olympics that we made race suits for were Nagano in 1998. It remained a very small company. It wasn't until 2007, when Canada started the Own the Podium fund, millions of dollars of funding that was going to innovation and support to help the Canadian athletes prior to the Vancouver Olympics in 2010, that I found myself taking an interesting & exciting plunge into race suit aerodynamics. I raced World Cup skeleton until I was 41, winning my last World Cup medal at 40 years old. Meeting Len Brownlie in a wind tunnel testing session while I was still an athlete literally changed my life. Len has become my mentor and a very good friend now. During meetings with the Own the Podium fund, he brought my name up on the matter of race suits, and this is how I was brought into this industry, the exciting world of innovation and was introduced to wind tunnel testing from a race suit design & fabric development standpoint.

Livia: How was it to be introduced to such a technical environment?

Deanna Panting: I'll be honest, in the first few meetings, I would sit there with engineers and wind tunnel experts, and they would say, "Well, can we do this...?", and they would come up with a word.

I was just like, "Absolutely", and I'd be writing down the word to look it up after to find out if I could actually do it! Luckily, they were big, fancy words for concepts I completely understood.

I think, in fact I know, that a huge advantage I have in this field is that I was an athlete. I understand what an athlete needs to feel when they put on a race suit. Growing up, I had always been involved with clothing, and I even wanted to be a fashion designer when I was younger. So, it turned out that being an athlete, loving clothing and understanding the construction and the science behind that, the aerodynamics... it all ended up guiding me into this little niche that I found myself in.

HIGH-PERFORMANCE RACE SUITS FOR ALL KIND OF SPORTS

Livia: What do you and your team do at Qwixskinz? What have been the first successes of the company?

Deanna Panting: Research and production. With all of the research leading to the Vancouver Olympics, ten out of Canada's fourteen gold medalists were wearing clothing I was either part of the R&D and the wind tunnel testing, or some grade up to the final production of it: that is where it started to actually tie it in together from doing the research and, instead of turning it over to whoever was making the suits for the teams, we would get them made as well. I ended up with this kind of multi branched system where we do fabric development, aerodynamic testing and then move to production. This avoids losing some of the innovation once it is the hands on someone who does not understand the importance of certain attributes of the suits.

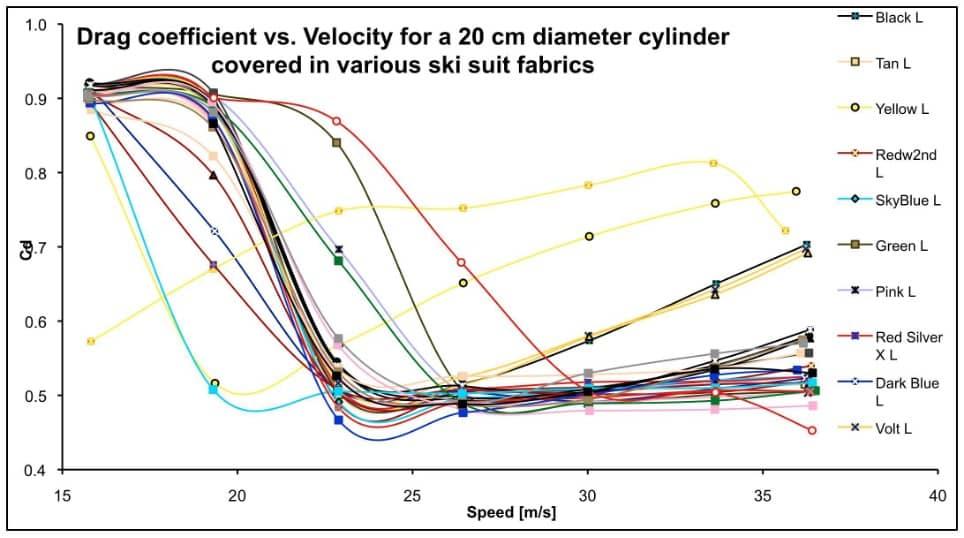

Generally, I'll be testing new fabrics in cylinder testing, which is how we always start. From there, we get an understanding of where we can potentially do larger scale testing for different sports based on what speed the fabrics end up being most beneficial at, and then it just progresses from there.

We work a lot with winter sports: we have been designing and improving the suits of the US speed skating team under the Under Armour label for example, whom we have just signed on for another four years. In the first years we focused on decreasing the weight of the suits by over 30%, and the air dynamic drag by over 5%.

![[object Object]](/_next/image?url=%2Fassets%2Fimages%2Fsuits_blog_2.jpg&w=640&q=75)

racer wearing a Qwixskinz suit.

Source: Viesturs Lacis.

We changed the fabric applications on different panels so that athletes could move better in a way that all their power could go into their skating as opposed to fighting the suit. Now we keep continuing that innovation. But I have also had the opportunity to work with other sports as well. Instead of just winter sports such as alpine skiing, skeleton and speed skating, which is our main focus, I have worked with the Canadian cycling team leading to the 2012 London Olympics, for example. For that project I was given the "code name" Edna, after the super suit designer from the animated movie the Incredibles! I am still called Edna by some people in the sports world. I love that I get to be that "super suit" designer in the background.

Livia: Are the suits only targeted at World Cup, Olympic & World champion athletes? Are they an option for alpine ski clubs or university level racers?

Deanna Panting: We supply suits to teams without doing additional or customized innovation. We have Qwixskinz production race suits that still test fastest in the world without added, specific innovation but it gets exciting when we get projects that sound like "How can we improve this?". I love answering "YES!"

People often come to me and say, "You found the fastest suit", to which I respond "No, as soon as you have developed a fast suit, there is a faster one to be developed!"

In speed skating, for example, there are some things that I am hoping to do in the next couple of years: everyone has been chasing what the Nike Swift suit innovated 20 years ago, but since then, there are faster fabrics and new beneficial ways of being able to give compression, muscle support and range of motion, as well as additional aerodynamics. It is the Holy Grail of race suits that I would love to develop & end my career with such a high note for the athletes we do all of this for. So that is the kind of step that we are going to see soon, and like anything with research, you don't know it until you test it but there are some VERY interesting ideas we are exploring at the moment.

ATHLETE AND TECHNOLOGY: FINDING A WINNING EQUILIBRIUM

Livia: What do you personally think about improving performance via technology? How do you see this from an "ethics" perspective: does it reduce the "purity" of performance or is it simply part of the game?

Deanna Panting: Sometimes you see science getting ahead of the athletes. I think that the science should never overshadow the athlete. I think you have to find the right kind of a balance. Everyone has to be very aware of the rules that come with every different sport and federations. You want to go up to that line, but you do not want to go over that line. There have been cases in sports where they pushed beyond the rule, and I do not agree with that. Our one job is to support the athlete to be their very best.

Livia: There are often limitations dictated by competition regulations that limit aerodynamic design freedom. Do you sometimes enter a grey zone in terms of the rules & regulations? Is finding loopholes part of the fun?

Deanna Panting: Loopholes & grey areas are sometimes where you find the next innovation. If it is not crossing the line, it is allowable until it is not. I try to find the line and I'll go right up to that line, because that is what is legal, and I won't go past it. Sometimes rules are changed after you find that grey area & then we dial back from what is now illegal in the sport but true innovation is in the area no one thought of & is usually not in the rules. One thing that my husband and I have always said that we love about our job is that we get to be part of every athlete's best day in sport, whether this is an Olympic gold medal, a World Championships, Special Olympics, or provincial level. Every athlete has a best day, and our job is to lift up the athletes by making suits so they can use their own ability and their own power to have a better performance. I don't agree with going past the line, and I have seen it in sports a few times. I do not want to be part of that. There is such a trust that athletes put in us, you know, you can't risk compromising their careers, and mine, by getting them disqualified. I simply want to be able to find the fastest fabric, the right texture, the right seam placement that helps to manipulate the air flow so that we have the least amount of turbulence on the key points.

Livia: How important is building the relationship with the athlete?

Deanna Panting: I work very hard to build trust with athletes I work with. You must have a relationship and you have to go through stages to earn their trust. And once they trust you, you can't break that trust. For example, one athlete, who is a world record holder and Olympic medalist, was my big puzzle because I couldn't figure out how to get the fit perfect on top of her shoulders and her upper back. And it wasn't until I watched her Olympic trials race where I carefully watched how her shoulders position on the start line, that I reworked her pattern based on what she does with her shoulders. I knew how to change it, and once she got the Olympic suit fitted, we gained that trust with her. It took time and effort, and I appreciate that is the moment the athlete recognizes that we work on doing what is the best for them. That time she went on to stand on the Olympic podium.

![[object Object]](/_next/image?url=%2Fassets%2Fimages%2Fsuits_blog_3.jpg&w=640&q=75)

wearing a Qwixskinz suit.

Source: Viesturs Lacis.

I have also worked with one athlete who's winning a gold medal was literally history making. The next day I got a text saying, "Thank you for the fast race suit". I get so excited to see athletes fulfill their dreams. And you know what? I am more excited to see what we can do to help athletes win their medals, than any medal I won myself. This tells me that I am working in the right field. I like being off to the side, watching athletes achieve and being very proud of them. Then we move on to the next project.

Aerodynamics is critical and we do obsess with it, but I have joked in the past that if we can make athletes believe they can win in a paper bag, they will win in a paper bag. The human brain is a fascinating component of the process of getting the fastest suit. Once the athlete believes they are wearing the fastest race suit that they could possibly wear, they own the suit and their performance. Once they put on the suit, it must feel amazing and fit perfectly that it has to make them feel like a superhero.

DESIGNING AND TESTING FOR AERODYNAMIC ADVANTAGE

Livia: How would you explain the aerodynamic advantage of the race suits?

Deanna Panting: Well, what we have found is that there are so many factors involved in the aerodynamics of race suits and how you reduce the drag. Basically, what we are trying to do is manipulate the air flow so that you get less dirty air or turbulence flowing off the body. Just like for an airplane wing, we want the air to come and follow the curves of the body. That is why we do cylinder testing: the body is nothing but a combination of cylinders.

Livia: Is improving the aerodynamics only relevant to high-speed sports?

Deanna Panting: It is interesting because I have worked with many high-speed sports, as well some lower speed sports. You would never think of lower speed sports getting the benefit of it, but say for example, I worked with Nordic ski and biathlon as well. Even in these sports, if you can reduce the athletes' aerodynamic drag, it takes less effort to move their arms and legs through the air. When racing a 50-kilometer race, if you have less effort for the arm and leg movement at a certain speed, it will make a difference.

One time, when we were testing a number of fabrics for Alpine skiing, we found one fabric that was terrible for the Downhill and Super G speeds of like 100 to 130 kilometers an hour, but there was this beautiful sweet spot in the 50 kilometers an hour. I looked at my diagram again, what we found was a great fabric for slalom skiing! For slalom, people often think speeds are too low to consider any aerodynamic advantage, but we say, "if air flows over the body and it is a time sport, aerodynamics matter, period." Additionally, in this case, athletes are going slower because they have to ski around gates so more "gates aerodynamics" matter, which we have looked at through CFD diagrams for example.

Livia: So you use some CFD in the process then?

Deanna Panting: Yes, I take any information that I can get, or I should say any accurate information, because that is the other thing that I have found in our time doing this work. For example, with wind tunnel testing, one needs to remember that not all wind tunnels are created equal. There are different factors and different benefits specific to each one, such as the data collection method; or the fact for example that some are great for cars, but when you are talking about using a wind tunnel with a balance set for a car and you are trying to put a180-pound athlete on it, it is not the same thing. I have not had a lot of opportunities with CFD but I am definitely hoping more chances arise to. I believe it can be a very valuable tool.

When testing in the wind tunnel, are factors such as temperature and humidity accounted for? How do you make sure test conditions will best represent those on race day and you don't end up with a suit perfectly optimized for wind tunnel only?

Well, this is a good question because so many people, and it is surprising how many times I have seen it done over the years, over and over again, where some company would make a great "wind tunnel" suit. However, you need to think about actual racing conditions.

When we were doing testing leading up to the Vancouver Olympics for skeleton, we built walls in the wind tunnel that replicated the walls of the track, as there was certain air flow that would come off the walls that you had to take into account. Or, in an opposite way, one time we moved Alpine ski testing from a smaller wind tunnel that we had issues with blockage ratio with, where the problem was having a big body into a small tunnel. That time we moved to another tunnel in Oshawa, the University of Ontario.

![[object Object]](/_next/image?url=%2Fassets%2Fimages%2Fsuits_blog_4.jpg&w=640&q=75)

a wind tunnel session.

I'm excited about seeing if in the future we can get more winter sports there because it was an open tunnel, where we could manipulate temperature and humidity within half a degree. Another thing that was great with that situation was that I actually did a fitting session at 130 kilometers an hour: I was standing in the tunnel, not in a control room as most wind tunnels can only accommodate. I stood just outside of the air flow, and I was able to see where we were getting wrinkling or where we were getting some vibration in the suit at the higher speeds. Then they shut down the air, the athlete stayed in position. I took my measuring tape and my notes and figured out what seams I needed to change. Peeled the suit off of them & altered the suit right there to make adjustments for immediate retesting. I always have a sewing machine at the wind tunnel. It was pretty cool because after I altered the suit to fit to achieve the optimal fit, we would put the suit right back on them and you could see the immediate drop in drag. This was probably one of the coolest sessions that I was a part of because you never get the opportunity to really see what is happening at 130 kilometers an hour with that skier. If I was standing on the side of the hill watching them fly by at the World Championships, they are a blur.

Livia: Do you take care of data collection?

![[object Object]](/_next/image?url=%2Fassets%2Fimages%2Fsuits_blog_5.jpg&w=640&q=75)

Deanna Panting: I'm not an engineer. Everything I have learned is from the smartest people I have ever met, and so, I rely on engineers anytime we go into a wind tunnel. I have worked with Len Brownlie on projects: he knows the data collection and all the calculations. I analyze the graphs and the charts and then make decisions from there. His reports are key to the decisions I have to make after the testing. It is critical to have clean data, and you have to make sure that everything that you are getting is accurate. Questions and doubts come up during the process and we have to figure out how to weed through them & have the accurate information to move forward. I don't believe in "change for the sake of change". Any & all changes need to actually be improvements.

Livia: Do you use the same wind tunnel for testing different sports?

Deanna Panting: It is interesting because what I always say to people is that I would love it if I could have like this multi $1,000,000 Aero fund to be able to just go in and spend weeks in fabric development in the wind tunnel. In reality, we are at the mercy of whatever federation or sports team approaches us.

Before COVID-19, I had a call from one Olympic Committee, and they said they wanted to do a multiyear multi-sport Aero program and they wanted us to be a big part of it. However, it stalled as soon as the pandemic hit. This was crushing because it would have meant being part of a project that finally combined sports to share data & ideas. It is crazy this is not prevalent in today's sports. At least it is not in North America.

In almost every nation, they have all these different sports and they are all doing similar developments & testing, but separately. If you centralized it, you would have got everything at the same wind tunnel where you would be getting clean and accurate data (you could be doing testing for skeleton and might find you have good data for luge or be testing speed skating and find improvements for cycling). It would be very efficient for sure.

Livia: What is the design cycle of the suits? What are the testing phases of fabrics, race suits designs, seam placement?

Deanna Panting: Well, I always start with the fabrics and testing different textures with cylinders. From that I can look at the graphs and see at what speeds the drag is increasing or decreasing. Then, we can take a look at each specific sport and each specific top athlete. For example, Mikaela Shiffrin (USA alpine skier) would potentially need a different suit than Steve Nyman who's heavier and is six foot three and hitting different speeds. This is just a theory until tested but it is currently not considered in that sport which is kind of crazy. But back to the process, once we have this information, we can start building the suit and study seam placement options. We can use the seams to either smooth out or make ridges. Then we go into the wind tunnel using a mannequin: the reason we use a mannequin is that we can get maybe an hour out of a person before they start to get fatigued but a mannequin can work all day & doesn't complain about being tired. It is critical, however, to make sure the mannequin used is accurate in size, proportions and body position. Finally, we bring the athlete in for fitting and testing. That is when we reassess everything and make adjustments to find the perfect suit in combination with all of their gear.

Livia: Do you take feedback data after race day?

Deanna Panting: Yes, we do that. We go into an analysis after race day, where we look at the results, the factors for those results, and then take a look at what we can improve from there.

Livia: Do you only consider static positions of the athletes or is movement involved as well in data collection?

Deanna Panting: It all depends on the sport. In a lot of them such as skeleton, you can do static. For speed skating, we try to use two different body positions of mannequins but we still have to keep in mind the time spent in each movement stage when making critical decisions. Same thing with Alpine ski. We like to test in the tuck position but also have to factor in the movement and half positions the archer is in for various portions of different race courses. It also depends on budget as it is not always easy to get access to another $20 to $30,000 to scan athletes & produce a test mannequin.

Livia: Do you consider only the suits or other gear in the wind tunnel testing?

Deanna Panting: Yes, we do also play around with other gear, say, if it is Alpine ski, the gloves, the helmet, or the goggles. They all have an impact on the aerodynamics of the athlete. You have to be open enough to be able to work with the athlete and all of their equipment. Bobsleigh has limited race suit aero needs as the sled is the major airflow factor. Skeleton & luge are combinations suit/athlete/sled/helmet.

Livia: How do you reduce drag on the suits?

Deanna Panting: Well, in indoor speed skating, we have used trips very successfully. When wind tunnel testing, I try to figure out a combination of dimples and trips on fabrics. However, trips are great if you have got no outside air turbulence. For indoor speed skating as there is not a lot of ice level turbulence, we found that a specific fabric has worked great. Now we are going to start to play with different variations in the depth of the lines & textures. How much can we stretch it? Fabric choice really depends on the sport and the speed at which the athlete is going at. If you find a great fabric which works perfectly at 60 kilometers/hour, it will generally not be as good for a suit of an athlete going at 120 kilometers an hour. There are two very different situations, and rarely you are going to find the same fabric composition and the fabric textures working on both.

Livia: Fabric choices mainly depend on tripping the flow to reduce drag or is there something else for what we prefer a fabric over the other?

Deanna Panting: Well, drag is generally the main thing we look at because that directly affects aerodynamic performance. Anytime we can, if we can see any way, we can manipulate the air flow to reduce the drag, that is the direction we are always going to go because again, if air is going over the body and we are dealing with a time sport, aerodynamics matter.

However, what we also try to do at times, without adversely affecting the drag, is working with compression or something that, depending on the sport, is going to positively affect the athlete's physical ability to race, whether it is supporting them in their body position, for example or offsetting vibration muscle fatigue. I believe our next generation of race suits will be able to improve an athlete's performance by improving multiple performance variables.

Livia: Do you look at thermal control to make sure, especially for winter sports, then the suit also keeps the athlete warm enough in colder temperatures?

Deanna Panting: We do to a certain degree. At the same time, if they are going to win a gold medal, most athletes will tell you they have no problem being cold as long as it is not so cold that they can't perform for those two minutes.

But it is always funny because sometimes there are rumors that go around in these fields. For years there was this rumor that in Alpine skiing, black is faster than white. And I was like, "Well, tell that to Lindsey Vonn because she won everything in a white suit." Or in speed skating, where people were saying that if the fabric was wet, the athlete would have less aerodynamic drag and, again, I was like, "Are you going to tell me that you are going to hose down a skater and get them to go skate?" Everything we do has to be within the concept of supporting the athletes so they can do their best. We cannot put them in a position where they are so uncomfortable, they can't perform, or they are so uncomfortable that their mind goes away from what they are supposed to be doing.

Livia: What about limitations to movements? The suits almost seem to always be very tight... do you consider freedom of movement of the athlete?

Deanna Panting: Absolutely. But at the same time, say both with Alpine ski and speed skating, where athletes are in similar tuck positions; the suit is designed to be aerodynamic in that race position, same thing with cycling. It cannot be too comfortable when you are standing up or it will be less than ideal in fit once in the racing position.

I remember some of the development athletes that we have worked with who are on their way to national teams. When putting on the speed skating suit "standing", they would notice the suits were rather "baggy" in the lower back. It looks funny but when I told them get into the skating position, the suits would fit perfectly. An ergonomically fitted suit is not made for you to be standing. Same thing with Alpine skiers. If you see them standing around it, it does not look great, but get them in their tuck position and that is where the fit is, even if sometimes this means that standing straight up is not the most comfortable thing. If they are more aerodynamic in their skating position, they will be happy to deal with that.

Livia: Do you use technologies tools such as 3D patterning and 3D scanning?

Deanna Panting: We do. One of the big things that made a huge difference for us, was the fact that we were able to do remote scanning for measurements. Because we can get all the "bells and whistles" in the 3D patterning process, but if we do not have the correct measurements, we could be making a suit for the wrong athlete. We could have the fastest suit in the world, but if it doesn't fit perfectly, it is not as fast as it can be.

Remote 3D body scanning has been a huge turning point in the last two years for us, because being able to use only two photos front inside to extract 75 measurements and get a fairly accurate 3D avatar is a great way to start working. And then we can utilize the 3D patterning, So we can look at wrapping the suit on the body. I'd love to be able to do that with the press of a button, but it is not as automatic as I hope one day it can be. I still have to go in and do a fit analysis, adjust patterns and customize the race suits. My job is not obsolete yet, which is probably a good thing.

These tools have greatly improved our work over the last few years. We are excited to see where we can take it in the next few years as I feel 3D patterning has some strides to take to be the game changer they claim to be but it is a good tool. You just have to know how to use it.

That, to me, means "what is ahead is even more exciting than what is behind", just because our tools & our testing are improving all the time... you know, it used to be that I would not take an order for a custom suit if I couldn't measure someone myself, but once we were able to do the remote scanning I have developed custom fit race suits for people as far away as Australia, Latvia, and so on. So this technology has completely changed our ability to do our job and that to me is very exciting.

We are also starting to set up databases for the top athletes we work with. In this way, we have a remote scan of their body at the beginning of the season, mid-season and then towards the end of the season, when they usually have World Championships or the Olympics. In almost every sport, athletes change their physique due to growing, losing weight, stress, getting sick, etc... to be able to then analyze the changes and adjust the suits here and there is a big advantage as we have to make sure that the suit fits perfectly for the most important day, which is always at the end of the season. It is exciting to me when we make these sorts of developments. I mean it adds to the workload, but that's okay.

Livia: What are the challenges of providing race suits for all levels of high-speed sports that require constant aerodynamic & fabric developments?

Deanna Panting: I think there are a few. One of them is budget. As I stated earlier, all of the ideas for innovation & race suit improvement would be much easier with a multi-million dollar pot to draw from but that is a dream currently. It is frustrating at times on our part because we are at the mercy of whoever has the funds and has the interest in making improvements for their athletes regarding their race suit. I am surprised at how many people in sport still do not give race suit aerodynamics the consideration it really deserves. I have been in the race suit business now for 25 years, and so I have seen it go from, 'keep me warm" in winter sports to "make me look cool", to "make me fast". I have seen that progression.

We have different levels of suits: for our highest level, an elite athlete, we do a 3D scan, we use 3D patterning... but if you take someone who is a 22nd place and you put them in the best suit, it will not magically put them on the podium. It is when you take someone from 4th to 1st or from 5th to 3^rd^, getting them on to the podium or changing which step the athlete reaches on the podium, that is where we put all our efforts in.

So, you also have to concern yourself with the credibility of what you are saying you can do. And that is where the algorithms and math models come up. I have heard some wildly exaggerated claims that we know, in aerodynamics, are not possible. I believe in retaining credibility & that is how you retain the athlete's trust.

Another challenge is even just human nature. The athlete's trust is very important, people just need to realize that we are here not to overtake their achievements but to add to it. I think science can be used to raise athletes up in their level of performance. However, sometimes athletes question whether or not you are going to be overtaking them. That is never my goal.

WHAT THE FUTURE HOLDS

Livia: What are the future areas of focus from the aerodynamics side to further improve sports performance?

Deanna Panting: Changes in seam placements and texture panels that I think can further improve aerodynamic drag. There are certain ways that I believe we can offset vibration and muscle fatigue. I am starting to work on a project I can't say a lot on, but I am trying to work on vibration muscle fatigue in combination with aerodynamics. This is something that has not really been done a lot in the couple of sports that I have targeted, but it is one of those things that I think would have a benefit.

Livia: What are you working on at the moment?

Deanna Panting: I am working on some new fabric developments that I am going to be testing soon. We are going to be looking at new applications in speed skating, skeleton, luge and bobsleigh.

We always work within Olympic cycles. Both 2026 and 2030 are upcoming targets. We will make the improvements for 2026, but we want to get the real innovation ready for 2030. We are raising the bar and improving with all of the sports that we work with. I think we have got some special developments coming up for a few sports. Soon there could be some real, big changes. It is a lot of fun to me, and this kind of research is what excites me the most!

Livia: Do you get to go to the Olympics sometimes to watch the athletes wear the suits you have made?

Deanna Panting: Well, it is funny because I get invited, but do not go very often. Once a suit development is done, I am on to the next project. I will always watch the races but just not from the stands.

A good example is when during the Vancouver Olympics, I was in Los Angeles working with cycling for the London Olympics. During the London Olympics, I was in the US working on a project for the Sochi Olympics. I would love to able to be right there and see it all happen, but it's very rare. However, I am hoping to be at the Milan Cortina Olympics in 2026!